Experts warn of Sperm Whale extinction risk in the Canary Islands

- 23-05-2025

- National

- Canarian Weekly

- Photo Credit: DIVE Magazine

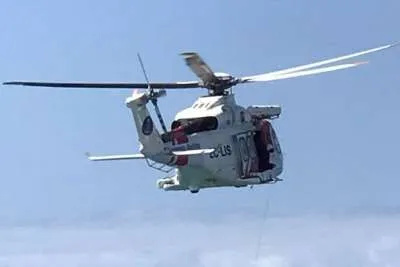

Marine researchers are raising concerns about the potential extinction of sperm whales in the Canary Islands, following the discovery of two more dead whales in the region’s waters in the last 24 hours.

Both of the dead cetaceans showed severe injuries consistent with propeller strikes from ships, a leading cause of death for this deep-diving species in the archipelago.

Dr. Natacha Aguilar de Soto from the Canary Islands Oceanographic Centre (IEO/CSIC) and Dr. Marc Martín Solá of the University of La Laguna have warned that the local sperm whale population is severely under threat unless urgent action is taken.

A Declining Population at Risk

One of the whales, a mature female approximately nine metres in length, was found washed up on a beach in Fasnia, on the east coast of Tenerife. Based on her size, researchers believe she had only recently reached sexual maturity and may have reproduced once, or not at all. The second whale, still drifting at sea, is believed to be a juvenile.

Sperm whales reproduce slowly, with females typically giving birth to no more than 10 calves throughout their lives. Gestation lasts between 14 and 16 months, followed by several years of nursing and maternal care. These whales live in matrilineal family groups that rely on the knowledge and experience of older females to identify feeding grounds.

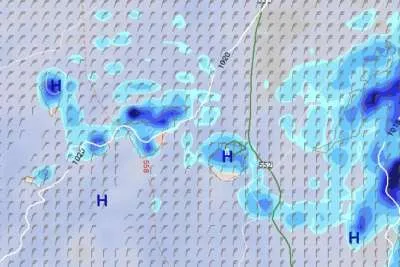

According to recent studies cited by Aguilar de Soto and Martín Solá, the Canary Islands population has suffered a sharp decline, with numbers halving in recent years. Although some whales continue to arrive from other parts of the Northeast Atlantic, the Canaries have effectively become an “ecological sink”: an area that appears ideal for the species but poses such a high risk of ship strikes that deaths outpace births.

Ocean Highways Endanger Surface-Resting Whales

Sperm whales, the largest predator in the ocean and the species with the largest brain on Earth, use powerful echolocation clicks to hunt in deep waters. To do this, they require prolonged surface rests, precisely when they are most vulnerable to passing ships.

The researchers note that in just one sperm whale generation, the average speed of vessels has doubled, and ship traffic in some areas has tripled. This rapid increase has created “high-speed highways” across the ocean, with little or no regulation in critical whale resting or breeding zones. The animals have become habituated to the presence of ships and ferries, often experiencing close encounters, until one proves fatal.

Resident sperm whale families have been identified in Canary Island waters for decades. Though the species is found globally, the decline in the archipelago is particularly severe and carries broader ecological and scientific consequences.

Aguilar de Soto and Martín Solá stress that the issue is not just biological, but also political and regulatory. Current maritime traffic management is failing to prevent repeated, fatal collisions.

They urge immediate measures to reduce vessel speeds, especially in known whale habitats, and to enforce stronger marine conservation zones in the Canary Islands, before it's too late to save one of the ocean's most iconic and intelligent species.

Other articles that may interest you...

Trending

Most Read Articles

Featured Videos

TributoFest: Michael Buble promo 14.02.2026

- 30-01-2026

TEAs 2025 Highlights

- 17-11-2025